| |

|

For a proper understanding

of the spiritual life and the nature of, and possibilities for, women’s

spirituality, we need a broader language of the spiritual than monotheism

can provide. The very term “transcendence” illustrates this

because in the Christian tradition it tends to have meaning in binary

opposition to “immanence” and refers to characteristics of

“God,” whereas in Eastern traditions—to the extent that

translation can succeed in finding corresponding concepts—it means

something closer to the “nondual” or “unitive.”

The “God”-language of the West has created a limitation of

understanding, both within religious and within secular communities, the

latter inheriting the equation “religion = God” and therefore

remaining ignorant of non-monotheistic religions. “God” is

a construct peculiar to Abrahamic text-oriented monotheism, and it needs

to be cut down to size, allowing other religious frameworks space. This

means that questions of spirituality and religion need additional, equally

powerful, terms to fill the gap. For women’s spirituality, the issue

is partly that “God” is an inevitably gendered term: monotheism

constructs a male “God,” served historically by a male priesthood.

Within the tradition of transpersonal psychology and its discourse of

spirituality, “transcendence” is now also a term under attack,

particularly by Jorge Ferrer. He suggests that the implicit adherence

to Perennialism—a term coined by Leibniz, popularized by Aldous

Huxley, and meaning a universal spirituality—within the transpersonal

tradition, creates a single conception of the goal of the spiritual life:

the transcendent (in the Eastern sense of the word). In a typically postmodernist

move, he argues that the spiritual life not only has a multitude of starting

points—not so controversial—but that it has a multitude of

goals: a radical proposition (Ferrer 144). In true postmodernist style,

he leaves open what these goals might be, which is to some extent a welcome

opening up of possibility. However, this actually leaves little more than

a flatland of potential with no landmarks, signs, or, even worse, any

powerful language that can stand its ground against the patriarchal language

of the “God” traditions. Instead, if “God” is

brought down from its dominant conceptual position, not to wander through

a relativist flatland as one among millions, it could take its place at

the table with just four other significant spiritualities. The

equal partners proposed here are shamanism, goddess polytheism, warrior

polytheism, and the unitive (transcendent).

Luce Irigaray, in her extraordinary little book Between

East and West, says, “There exists [in India] a cohabitation

between at least two epochs of History: the one in which women are goddesses,

the other in which men exercise a blind power over them” (65). It

is suggested here, instead, the sequence comprises five epochs:

shamanism, goddess polytheism, warrior polytheism, monotheism, and the

unitive. These will be presented as having a historical basis, but beyond

that, they are also archetypes of powerfully different spiritual impulses,

recapitulated within all people at all times. Like the Jungian archetypes,

they are conceived of as universals, which may come into play more in

one individual than another and more in one culture than another. In other

words, these five “epochs” of religious manifestation are

also five personal spiritual impulses, or five modalities of the spirit.

This articulation of spiritual difference through five historical modalities

is not to be read as a development from a lesser, more primitive early

modality to a higher, more sophisticated later modality. In other words,

it is neither Hegelian, which would imply an inevitable historical vector

privileging later periods or peoples, nor is it Wilberian, which would

imply a developmental psychology, which is assumed in the work of Ken

Wilber. This discussion of the earlier modalities of the spirit is informed

by anthropology, ethnology, archaeology, and the ancient literatures,

all of which disciplines are subject to new findings, methodologies, or

better translations. Simone de Beauvoir, Sigmund Freud, and Carl Jung,

to take some examples from the first half of the twentieth century, were

profoundly influenced by the anthropology of their day, making many assumptions

that would now be discredited by later developments in the discipline.

Voltaire, writing in the eighteenth century, was even more constrained

by anthropology at its birth. Similarly, some of the approximate dates

given here, or even possibly some of the major transitions alluded to,

may well have to be revised in the future. However, the modalities of

spirit that we are exploring in this historical fashion are not so dependent

on the detail of history, but rather their relevance hinges on whether

these modalities are archetypally present in our psyches today. We know

that contemporary Western city-dwellers actively take up ancient religious

practices (neoshamanism or neopaganism, for example) or adopt Eastern

unitive traditions (Yoga, neo-Advaita, or Zen, for example). The flourishing

nature of these adoptions illustrates the ability of people to respond

at a very deep level to modalities of the spirit that are remote in time

or place from their contemporary setting.

The Five Stages of Religion

Here five stages in religion are introduced as an idealized “photofit”

composite of world spiritual history, though the complete sequence does

not in fact exactly take place anywhere in the world: It is more a psychogeography

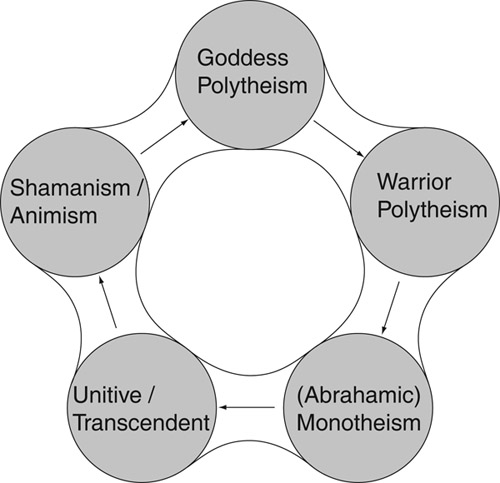

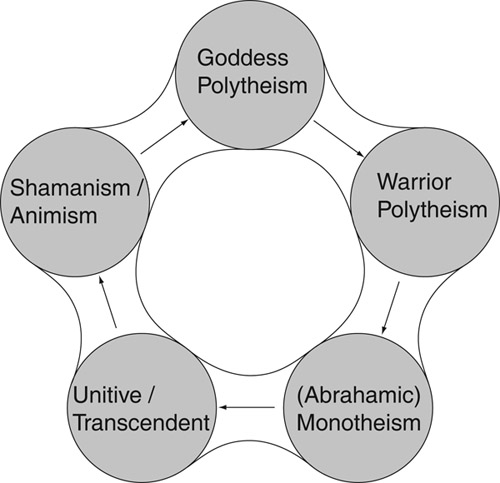

of the spiritual. These religious stages are can be shown diagrammatically:

Fig. 7.1. Five religious stages

The diagram has been drawn with curved lines to suggest that the boundaries

between the five modalities are fluid, even where, in the case of monotheism,

it strenuously resists other modalities of the spirit. Arrows have been

drawn to indicate the historic progression, with one exception: the arrow

from the unitive/transcendent to the shamanic/animist, which appears to

point backward in time, and will be discussed later.

Shamanism/Animism

The shamanic/animistic category represents a modality of the spirit that

seems to have emerged with humankind itself. No early hominid traces seem

to have been found without evidence of shamanistic practices, which include

artifacts—such as fetishes and totems—for rites that revolve

around Nature and “spirits.” The shamanic worldview is predicated

on a perception of Nature as imbued with spirit, wherein the elements

of Nature, such as rocks, mountains, trees, rivers, animals, and skies,

are inhabited by spirits and daily life is also filled with the presence

of the spirits of the ancestors. This “spirit world” is both

beyond the so-called material world and, at the same time, intimately

entwined within it: They are not separable in shamanism. Some scholars

believe that there is a meaningful distinction between animism and shamanism

in that the latter is served by a functionary or specialist called a shaman,

whereas the former is not. For our purposes, this distinction is of little

use. This is because both animism and shamanism, as they are generally

understood, are grounded in the same spiritual interiority of the spirit

world. In an animistic culture, there would surely exist individuals whose

gift for entering into the spirit world was more developed than others

and who would naturally take on roles of intercession and healing, though

perhaps not culturally formalized in the way that shamans are. Conversely,

in a shamanic culture it is inconceivable that the rest of the group would

not mostly share the worldview and spiritual abilities of the shaman,

at least in a nascent form. Hence, we will from here on use the term “shamanic”

to cover both animist and shamanic spiritualities, though we are referring

more to an inner orientation or sensibility than to outward ritual or

practice.

The shaman, who can equally be male or female (as shown in traditions

as far apart as in Siberia and South America), is required to mediate

between the group and the spirits as the functionary of this religion;

conversely, he or she makes the world sacred through the practice of ritual.

Shamanism is associated with hunter-gatherer cultures, and though it is

understood as the universal ur-religion of mankind (proposed, for example,

by Mircia Eliade in his seminal work Shamanism: Archaic Techniques

of Ecstasy), the word “shaman” itself comes via Russian

from the Tungus people of Siberia (or it may have its root in Sanskrit).

We are fortunate that shamanism has survived at the margins since the

earliest of times, generally driven to unfertile or inhospitable territories

by later agricultural societies. Hence, in mountains, deserts, or polar

regions, shamanic cultures persist to this day (though increasingly ravaged

by their contact with the industrial world) whose practices and beliefs

can be studied.

A form of neoshamanism has recently emerged, particularly in the United

States, as people with little previous interest in religion take up shamanic

practices under modern teachers or guides. The writings of anthropologist

and cult author Carlos Castaneda and the work of transpersonal psychologist

Stansilav Grof have been significant in this revival. Michael Harner,

author of the classical work The Way of the Shaman, comments

in the tenth-anniversary edition on a “shamanic renaissance”:

“During the last decade, however, shamanism has returned to human

life with startling strength, even to urban strongholds of Western ‘civilisation’,

such as New York and Vienna.… There is another public, however,

rapidly-growing and now numbering in the thousands in the United States

and abroad, that has taken up shamanism and made it part of personal daily

life” (xi). Shamanic peoples often display a certain gender fluidity

and gender balance, despite the roles of men as predominantly hunters

and women as predominantly gatherers. Males of shamanic cultures often

look feminine by modern Western standards, while females may not have

our contemporary exaggerated femininity. Neither do these men and women

have the individualistic or egotistic natures of Western people; perhaps

this has led to the widespread but absurd notion that shamanic peoples

have a less developed personal consciousness. A better way to understand

a defining characteristic of shamanic peoples is as self-effacing.

Good portrayals in contemporary culture are to be found in the character

played by Chief Dan George in Clint Eastwood’s film The Outlaw

Josie Wales (1976), Old Lodge Skins in the film Little Big Man

(1970), or in the character of Dersu Uzula in the film of the same name

by Ikuru Kurusawa (1975). Well-known Native American actor Gary Farmer

plays “Nobody” in Jim Jarmusch’s film Dead Man

(1995), vividly conveying the humility at the heart of the Native American

way of life and what is arrogant in that of the white man.

Goddess Polytheism

If “shamanism” is a contested term, then anything to do with

“goddess” is doubly so. There is in fact a genuine difficulty

in the discussion ahead: Shamanism has survived in the margins, has been

extensively studied, and so is at least in principle recoverable as an

ancient practice. But goddess religions—to the extent that we now

posit their existence—were systematically eradicated by later modalities

of the spirit and had nowhere to go. There is growing evidence

from archaeology that Goddess cultures replaced shamanic hunter-gatherer

cultures in all parts of the world bar the marginal lands around the period

of the late Neolithic and early Bronze Ages (Shlain 35). But the interiority

of this modality of the spirit is more problematic and less recoverable

than the shamanic because there is no surviving unbroken tradition. Instead,

there is a modern revival, led by radical scholars, such as Starhawk,

along with women from all walks of life, who seek to imaginatively reconstruct

this spirituality. It is the archaeological evidence and the modern revival

taken together that make the case for Goddess Polytheism as a

major modality of the spirit.

In spiritual terms, we can identify two stages in the transition from

hunter-gatherer cultures to agrarian ones: first, to “goddess polytheism”

and then to “warrior polytheism.” Both involve an increasing

process of abstraction in the conception of spirits or deities. The hunter-gatherer

way of life existed for possibly some three million years, and, as a first

approximation at least, we can associate the shamanic modality of spirit

with that way of life. The implication is clear: shamanism must be deeply

rooted in the human psyche if it were present over such huge timescales.

Hunter-gatherer societies in general seem to have been nonsexist and relatively

nonviolent, comprising family groups of about eighty to a hundred individuals,

all well known to each other. Some seven thousand years ago, two new skills

emerged: that of animal husbandry and that of agriculture. Whether as

horticulture (small-scale agriculture) or as agriculture proper, the new

way of life spread rapidly and pushed the older hunter-gatherer lifestyle

to the margins, along with its central spiritual form: shamanism. Baring

and Cashford suggest that we can broadly associate goddess polytheism

with small-scale horticultural communities of the late Neolithic and early

Bronze Age, and warrior polytheism with large-scale agriculture and societies

of the later Bronze and Iron Age (416).

The growing scholarship on goddess religions is led by feminist archaeologists

and thinkers, whose role as feminists in this is to uncover the layers

of patriarchal prejudice that have clouded the disciplines of archaeology,

anthropology, and history up to very recently. For example, the huge quantities

of goddess figures unearthed in archaeological sites all round the world

were routinely dismissed as products of “fertility cults”

by male (Christian) academics. Merlin Stone’s When God Was a

Woman is an early but superb account of the endemic and often subtly

propagated male prejudice in these matters. Once the same data are looked

at from the recognition that goddess religions were not marginal cults,

but central to thousands of years of human history, a radically different

picture emerges. We can say that the word “cult” is a quick

way to dismiss anything non-Christian and the word “fertility”

a quick way to dismiss anything nonmasculine; hence, “fertility

cult” conveys total contempt in the mind of the male (white) Christian.

The work of Marija Gimbutas, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, and Starhawk

(born Miriam Simos) are seminal in this field, while author Leonard Shlain

contributes radical proposals about the marginalization of goddess spiritualities

because of writing.

In the period of goddess polytheism, the discrete, specific, and localized

spirits of the shamanic world took their first steps into abstraction

as gods and goddesses of early horticultural life. These deities were

propitiated perhaps in a different way than in shamanic culture. As less

specific spirits and more abstracted deities, the spiritual response to

them would have changed, perhaps quite dramatically (Hillman xxi). The

shamanic mode of “storytelling” becomes a polytheistic mode

of “myth”: a transition from an animistic engagement with

living spirits to a mythic engagement with psychic entities. It may also

be the case that goddess spiritualities were more centered on human-human

relationships than human-animal relationships. We have emphasized the

polytheism in goddess spirituality: This is to counter the Western

cultural impetus to merely transpose a male monotheism into a female monotheism,

a single “God” into a single “Goddess.”

Scholars such as Leonard Schlain and Marija Gimbutas now believe that

the entire Greek mythology can be understood as arising from the transition

from a goddess culture to a patriarchal polytheism, undertaken at the

time when oral traditions were first transcribed in the new Semitic alphabet

(Shlain 120). Possibly the best illustration of this transition in contemporary

culture is to be found in the film Medea (1969) loosely adapted

by Pier Paolo Pasolini from the play by Euripides, featuring the opera

singer Maria Callas in the lead role (her only film appearance). Medea

represents for Pasolini the transition from matrilineal, goddess cultures

to patrilineal male warrior cultures as she returns with Jason, whose

mission it was to steal her golden fleece. Pasolini captures the moment

of transition as the Argonauts land in Corinth on a simple raft. Medea

cannot understand how the men treat the land of their birth: They do not

call to the ancient deities, propitiate the nature spirits of earth and

stone; they merely tread on the land as property. She is overcome

and then rants at them, full of passion and foreboding: “This place

will sink because it has no foundations. You do not call god’s blessings

on your tents. You speak not to god. You do not seek the centre; you do

not mark the centre. Look for a tree, a post, a stone.”

Once on the soil, which is now to be her new homeland, she runs in despair

through the grasses, wailing: “Speak to me Earth, let me hear your

voice, I have forgotten your voice. Speak to me Sun. Where must I stand

to hear your voice? Speak to me Earth. Speak to me Sun. Are you losing

your way, never to return again? Grass, speak to me. Stone, speak to me.

Earth, where is your meaning? Where can I find you again?”

To monotheists, steeped in the Old Testament proscription against idolatry,

and the wider and endemic scorn within the Old Testament toward the older

Nature religions, Medea is merely a pagan among pagans: What is her objection

to the paganism of the warriors who take her home? But to those whose

spiritual antennae are attuned to the differences between shamanism, goddess

polytheism, and warrior polytheism, her anguish has a clear and obvious

source: the new, patriarchal polytheism is abandoning Nature and substituting

instead more abstract “gods”—those whose interest is

only in the narrowly human and the warlike at that. Later in the film,

Pasolini makes clear the extent of Medea’s spiritual tragedy:

Centaur: Despite all your schemes and interpretations,

his influence causes you to love Medea.

Jason: Love Medea?

Centaur: Yes. Also you pity her. You understand

her spiritual catastrophe. A woman of an ancient world, confused

in a world which ignores her beliefs. She experienced the opposite of

a conversion and has never recovered.

Jason: What use is this knowledge to me?

Centaur: None. It is a reality.

Pasolini both understands Medea’s “spiritual catastrophe”—and

it stands for the spiritual catastrophe of all women as they came under

the subjugation of patriarchal tradition—and makes it clear that

Jason is utterly uninterested. It is a reality of Medea’s life,

not his.

In this context, then, it is of interest to turn to Irigaray’s

concept of the “aboriginal feminine,” as discussed in Between

East and West. This is a most useful term, though it needs a little

elaboration in the context of the epochal spiritualities proposed here.

Irigaray had found in India, at the time of her 1984 trip, signs indicating

that an ancient feminine spirituality survived alongside later patriarchal

religion, particularly in the south (this is the remnant of the original

Dravidian culture driven southward by the invading Aryans of the north).

Effectively, India allows us to see today a palimpsest of the historical

transition that took place in ancient Greece and so effectively dramatized

for us in Pasolini’s Medea. But what Irigaray practiced

in India and brought back with her to the West was Yoga, a spiritual tradition

as ancient in epochal terms as Medea but exclusively located within the

unitive/transcendent modality of the spirit. Hence, she is quite right

to question the apparent genderlessness of Yoga as a discipline and a

teaching of transcendence.

Warrior Polytheism

As large-scale agriculture developed out of small-scale horticulture,

methods of creating surplus came into being through the cultivation, drying,

and storage of grain: This became the first form of wealth and wages.

Eventually, this led to the emergence of the city-state and created a

radically new way of life over the small-scale horticultural community.

Complex social and economic patterns emerged that allowed a class of society

to live removed from the immediate production of food. At the same time,

there had evolved a new sphere of male human activity: warfare. Leonard

Schlain believes that the Neolithic and early Bronze Age period from approximately

ten thousand to five thousand years ago seems to have been dominated by

women, with little militarism or central authority, but the male hunting

instinct seems to have been transforming itself during this time into

the instinct for war (Shlain 33). Perhaps as crops required defending,

not just from wild animals but also from other tribes, defensive and then

offensive patterns of aggression developed. With economic surplus and

the development of settlements into cities, a military caste came into

being, and with it what we are calling “warrior polytheism.”

Society became stratified in a way that was impossible during the epochs

of hunter-gatherer and Goddess societies, leading also to a new priestly

caste. The shaman might be called the “priest” or “priestess”

of the shamanic way of life, but his or her powers were in healing and

in shamanic flight: The new priesthood became guardians instead of great

temples and therefore also of wealth and power.

Warrior polytheism continues the proliferation of deities, along with

the tendency to anthropomorphism (as opposed to the taking on of animal

characteristics within Shamism: zoomorphism), but in the patriarchal pantheon,

the female deities were demoted or forgotten in favor of new male ones.

(They were literally “written out” of history.) Ancient Greece

provides us with a good example of how the new deities were considered

to be as quarrelsome as the war ridden human city-states. The key issue

here however is the shift from a female-dominated culture and religion

to a male-dominated culture and religion: from matriarchy to patriarchy.

The flowering of goddess cultures between seven thousand and five thousand

years ago was brought to an abrupt end in the Mediterranean world at least,

and historians and anthropologists have argued over the causes for more

than a century. (In India, as Irigaray saw, there are still vivid traces

of the earlier modalities of the spirit.) What brought patriarchy into

being is of interest generally, but in terms of religion, the shift was

nothing short of a revolution. Shamanic spirituality was equally male

and female; Goddess Polytheism was female dominated; but all later religion

became male dominated. Shlain considers Engels’s theory that the

growing concept of property favored patriarchy but refutes it on the basis

of many property-based goddess cultures. Shlain suggests instead that

patriarchy arose with writing and in its most radical form with

the linked inventions of the alphabet and monotheism. He bases this on

his understanding of the brain (he is a neurosurgeon by profession) and,

in particular, on the division of functions between the left and right

hemispheres (Shlain 23).

Agriculture led to the stratification of society and to the division between

those who worked on the land (and who probably retained their shamanistic

practices) and the city-dwellers, who began to live at one remove from

nature. The city-dwellers needed more symbolic thinking to deal with the

increased social, technical, and political complexities of their lives,

and, hence, the process of increased abstraction was necessary. One of

the qualities of polytheism is the tendency, possibly inherited from its

shamanic roots, to be localized; that is, for gods to belong to regions.

Hence, the Romans, in administrating their conquests, acknowledged the

local gods and allowed their worship as long as the gods of Rome, particularly

the Emperor, were included. (The Jews were a notable exception in the

Empire, refusing to cooperate with this.) In fact, the gods in different

cultures were rarely so different as to be unrecognizable. Caesar, for

example, had no difficulty in finding the Roman equivalents to the deities

he discovered in conquered Gaul. (This is a process referred to by an

early meaning of the word syncretism.)

To contemplate what a warrior polytheistic modality of the spirit might

feel like, we can turn to the early Roman, Greek, Mayan, or Hindu cultures

and enter imaginatively into the life of those early city-states. It is

a world of myth making, a mythology that holds within it a great departure

from shamanic storytelling: It is heroic and, in its Greek form,

also Oedipal. The shaman is amorphous and self-effacing (also

androgyne), whereas the polytheism of the city-state serves its principal

activity: warfare. Of course, when the heroic emerges onto the world stage,

so does the hubristic: success and failure enter the vocabulary in a way

unknown to shamanic and goddess cultures. Tragedy is born with “civilization,”

articulated in the Greek myth of Oedipus, as the inevitable competitiveness

of the son with the father. When Freud took this story to be a universal

of the human mind, he was operating only within the Western inheritance

of Greek warrior polytheism. The Far East arrived at its patriarchy in

a rather different way: The Chinese mind would not have made a drama out

of Oedipus’s killing of his father and marriage to his mother, both

unintended. “Such things happen in the realm between heaven and

earth,” is a more likely response. (Interestingly, Pasolini also

chose to make a film out of the story of Oedipus: Perhaps, as a homosexual,

he was much interested in the origins of Western masculinities.)

Although much of the modern mind is born out the polytheistic context,

including its rejection of the shamanic, our Western cultural heritage

of monotheism makes polytheism seem like a distant form of consciousness

for us. Psychologist James Hillman has recognized this and the psychological

need for an essential component of polytheism: its pluralism. He suggests

that the psyche, instead of striving to some imaginary unity in the image

of the single “God,” should celebrate its multiplicity of

impulse in terms of the “gods,” plural, as a better reflection

of the polyvalence of the human mind (Hillman 30).

Monotheism

When considering Abrahamic monotheism as a modality of spirit, among other

equal epochal forms, it is perhaps useful to point out the following:

It is geographically unique, arising in the Middle East and nowhere else

in the world (it is hence an anomaly on the world stage of religions);

it evolved from warrior polytheism, not goddess polytheism; it is associated

with a horrifically violent rejection of earlier epochal forms; it is

patriarchal; it is associated with the invention of the (Semitic) alphabet;

its “God” is not localized, and it becomes a religion uniquely

associated with the written word (giving rise to “language mysticism”).

Monotheism retains the idea of “God” as a being, a supreme

being, analogous with just one of the previous gods but somehow incorporating

the separate characteristics of all of them. Anthropomorphism, that is,

the tendency to project human qualities onto the polytheistic gods, is

fiercely resisted in Judaic monotheism, with its prohibition on speaking

the name of “God,” and the denial of attributes to him. However,

it is not surprising that a single “God” becomes anthropomorphized

in the popular mind, however much this tendency is resisted, and this

problem is central to the history of monotheism. Judaic, Christian, and

Islamic monotheisms are intolerant of other gods, but in other cultures,

a pseudomonotheism has not excluded polytheism. Brahman, for example,

the “God” of the Hindus, is worshiped through a plethora of

other deities who are understood to represent one or more of his divine

aspects. Hence, we cannot say that Hinduism is exclusively monotheistic

or exclusively polytheistic. In fact, Westerners have read their Judeo-Christian

“God” into Brahman in a quite inappropriate way. Similarly,

Jesuit missionaries in China persuaded themselves that the Chinese “heaven”

was the equivalent to the Christian “God,” though their fellow-missionaries,

the Franciscans, thought otherwise and finally convinced the Pope to come

down against the Jesuits (Paper 5).

The idea of monotheism seems to have emerged in four possible locations:

in fourteenth century BCE Egypt with Akhenaton; in Northern Africa (Barnet);

in Persia (modern-day Iran) as Zoroastrianism in the sixth century BCE;

and in Israel, as an ongoing process of change that may have been influenced

by the Egyptian and Persian examples. Although Egyptian monotheism was

rapidly overturned, and Zoroastrianism became a tiny religion on the world

stage, it was Judaic monotheism that has had the most impact on the world,

through its influence on Christianity and Islam.

The Transcendent/Unitive

In the final development of the religious life, monotheism becomes a transcendent

or unitive religion, represented for example by Buddhism and the concept

of nirvana. However, there is no simple example of a monotheistic

religion developing into a transcendent one; for example, in the case

of Christianity and Islam, the mystics who entered into this form of the

spiritual life were generally persecuted. Meister Eckhart is an example

in Christianity who was condemned by the Inquisition, though he died before

any punishment could be inflicted, while Mansur (Al-Hallaj) is an example

in Islam who suffered a horrible martyrdom. In both cases, the problem

for their mainstream religions was that their understanding of “God”

had gone beyond the notion of a separate being: their unitive experiences

calling for a language of personal transcendence foreign to monotheism.

The position of the mystics in the Judaic tradition is more complex, in

that they tended to avoid personal declarations of union, and in any case,

any popular anthropomorphism of “God” was balanced by its

continual denial in the writings of Judaic scholars (Scholem 63). As a

result, the “transcendent” is generally the most difficult

component of the spiritual life to describe, particularly in the West.

The term “unitive” is equally good but not as familiar. The

East has the well-known concept of “enlightenment” (or nirvana,

moksha, or liberation), which describes the goal of the transcendent

religionist and a transcendent religion. It is “unitive” in

the sense of “not-two” (as in Zen and Advaita formulations)

but not conceived as union with “God.”

If read in a literal developmental sense, these five stages do not map

onto the religious history of the world in any simple way. It is clear

that by at least 2,600 BCE all five stages had already emerged onto the

religious world scene, though our historical knowledge of this, and earlier

periods, is rather sketchy. In both the Mediterranean and Indian cultures

of that period, we find evidence that all five strands—shamanism,

goddess polytheism, warrior polytheism, monotheism, and the unitive/transcendent—were

present and to one degree or another available. This means that

individuals, depending on their circumstances and mobility, were able

to draw on the support for different types of spiritual life. The extraordinary

richness of the spiritual life around the Mediterranean at the time of

Christ, for example, shows how all five types were present among the different

cultures and social strata. This is well documented in The Jesus Mysteries

by Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy. In India, too, by the time of the Buddha,

there was a similar spread of religious practice, and in the ancient Vedas

and Upanishads, we find a recognition that is central to the discussion

here: Each individual tends to gravitate toward the spiritual life that

suits them. More than this, each individual has a spiritual impulse and

temperament that aligns itself within these categories and has a right

to adhere to them without interference. Such a right was never part of

the Christian history of the West.

That an individual has a right to pursue the spiritual life appropriate

to them was of course never enshrined in the ancient world either in law

(human rights are a recent development), or very often in opportunity

(economic and geographical mobility was limited). Nevertheless, those

who devoted themselves to the spiritual life in the ancient world often

traveled large distances to seek out the teachings they could not find

locally, and a large part of ancient discourse resulted from such travelers

bringing back new teachings (Pythagoras being a good example, or Solon

in Plato’s Timaeus). This is of course quite obscured from

the secular Western mind so shaped by Christianity. By denigrating all

the spiritual traditions previous to Christianity as “pagan,”

a monolithic and exclusive understanding of early religion held sway.

The hostility toward shamanic and goddess spiritualities also came from

the Greek inheritance, though, in this case, it is more a question of

a prejudice against those people living in the countryside and working

the land and against women. The legacy of this prejudice is still highly

visible in the United States and the United Kingdom and in the productions

of mainstream Western culture.

The transcendent needs a little more explanation at this point. We have

implied that it would develop out of monotheism, and in fact, we see many

examples of the transcendent impulse in Christian and Sufi mystics. In

the transcendent spiritual experience, “God” as “other”

gives way to a state of union or identity and, hence, ceases to be thought

of as a “being,” even as a “supreme being,” rather

as simply the “being” at the core of the mystic’s identity

(Eckhart is a good example of this). In Buddhism, there is no concept

of “God” to start with, just the extinguishing of the separate

sense of self (“not two” in the formulation of some Zen traditions).

It is not possible in a brief overview to develop this very difficult

idea fully, but we leave it for now with two remaining comments. First,

that the Christian mainstream did not easily tolerate the transcendent,

any more than it did signs of “paganism.” Second, to counter

the simplistic notion that there is a linear spiritual trajectory through

the five types of spiritual life, we might look at the example of Tibetan

Buddhism. It is the result of the integration of a shamanic religion (the

Bon tradition of Tibet) and the incoming Buddhist teachings of transcendence.

The two live side by side and create a spectrum of spiritual teachings

that support a wide range of spiritual temperaments, an example again

of spiritual pluralism within a single tradition. We have characterized

Christianity as monolithic, but it is not completely homogeneous, rather

the permitted range of spiritual expression is narrow compared with Tibetan

Buddhism, for example, and even narrower when laid side by side with Hinduism.

The arrows drawn in our diagram from shamanism to goddess polytheism and

so on can be read as implying a developmental sequence or even an inevitable

sequence. This is not the intention: it just so happens that elements

of this sequence can be found everywhere in history. But we have drawn

a final arrow from the transcendent back to the shamanic, partly to counter

any sense of inevitable historical development and partly to highlight

how the shamanic and the transcendent so easily coexist in the East. Tibetan

Buddhism is one example, while the coexistence of Zen and Shinto in Japan

is another. The arrow linking the unitive or transcendent with shamanism

also suggests an engaged enlightenment: a Buddha who turns again

to the world.

Conclusions

To recapitulate: while the five religious modalities can be seen to form

a historical development, this sequence tends to privilege one form over

another. A better use of the distinctions between these forms is to understand

them as expressions of five different types of spiritual impulse, as archetypes

that are universally present. These impulses may arise in individuals

with no regard to history or the prevailing religious form, often leading

to a spiritual dislocation between individual and culture.

This fivefold schematic allows us to place monotheism in a global and

epochal perspective. Although monotheism is a significant modality of

the spirit and can be understood as an experiment in spirituality that

has created much of value, it has actively denied the other four modalities:

In particular, it denies the feminine. However, when the monotheistic

“God” is cut down to one-fifth of its claim and takes its

seat at the table with the other modalities, it can be a good partner.

For the survival of the planet, we need to actively explore those modalities

of the spirit that are nonpatriarchal, nonheroic, and that actively elevate

the feminine and a profound relationship with the natural world.

We can illustrate these points by considering Irigaray’s call, both

in her chapter in this volume, and in her book Between East and West,

to identify a “culture of two subjects”—male and female.

She says, “Each subject requires a different manner of becoming

divine,” perhaps corresponding to the two epochal spiritualities

that she detected in India (Irigaray 65). This idea in itself represents

a complete revolution, particularly for the West: It represents a spiritual

pluralism denied for millennia. But the scheme presented here cuts the

corpus in a different way by suggesting five different epochal

spiritualities, not in the first instance distinguished through gender

difference. Irigaray suggests two, Jorge Ferrer suggests an infinity,

and this chapter suggests five. Let us see how this works in an issue

raised by Irigaray in the specific context of the Yoga tradition. She

found herself acknowledging its apparent openness to women but quickly

discovered: “Because of this lack of cultivation of sexual identity,

the most irreducible site of reciprocity, reciprocity often seems absent

to me in the milieus of yoga” (66). Rather than just understanding

Yoga as a patriarchal spirituality, the fivefold scheme presented here

quickly locates it in the unitive/transcendent epochal form. Its core

text is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, which, as Irigaray has

picked up on, is disinterested in the question of sexual identity. It

also has as its core directive the “cessation of the mind”—a

very difficult concept for the West—which can be translated as a

“restriction of the fluctuations of consciousness” (Feuerstein

26). For Irigaray, this manifested itself in the instruction from her

Indian male Yoga teacher “not to think.” Such a teacher is

rather unlikely to understand the Western feminist tradition, which leaps

on such an exhortation as a patriarchal move to suppress the female. Irigaray

muses on this exhortation: “This [Yoga] tradition seems to me to

possess a subtlety that demands, on the contrary, a real aptitude for

thought” (Irigaray 67). Certainly, the Yoga tradition contains this

contradiction, but ultimately, it is a discipline of transcendence that

requires cessation of modifications of the mind (or fluctuations of consciousness).

These modifications ultimately include all discursive thought and gender.

Hence, the Yoga tradition, however modified for the West, cannot meet

Irigaray’s need for a “manner of becoming divine” for

the feminine, particularly because of her emphasis on the relational.

The unitive/transcendent is precisely an epochal or archetypal spirituality

in which the relational ceases. So, in our scheme, Irigaray would need

to turn to the other four principal modalities of the spirit to discover

where the appropriate relational spirituality might lie. In shamanism,

this relationality is mediated through the spirit world, and is ancestor

and Nature centered. In goddess polytheism, this relationality is propitionary

but locates relationship more within the human world. In warrior polytheism,

relations are mostly between men and male gods; divinization is in the

context of conquest. And in monotheism, the core relationship is between

self and the “wholly other”: “God” (Otto 25).

To be restricted to only one modality of spirit by the accident of birth

was a specific tragedy of the West. This is now overcome in the multivalency

of our postmodern world. Irigaray’s search for spiritualities that

serve a “culture of two subjects” is one expression of this

spiritual pluralism, Ferrer’s infinity of goals another. The scheme

presented here cuts down the “God” religion of the West to

take its place along four other major epochal or archetypal forms: Each

represents a major clustering of spiritual wisdom, of means of divinization,

of modalities of the spirit. The “accomplished interiority,”

which Irigaray elsewhere suggests should be the goal of the spiritual

life (37), may well even be achieved by a systematic exploration of all

five. Perhaps even in a single day, the human spirit needs to move between

these different spiritualities, as it does between different relationalities.

One does not live in the pocket of one’s sexual partner; one does

not spend all day with the ancestors, or in Nature; one does not devote

all one’s energies to conquest or horticulture; one does not even

need “God” all day long: a time for the cessation of all

mentation is also needed. Eckhart showed that most vividly (159).

But such an easy pluralism may be a long way off for a society still struggling

to shake off the habits of thought formed by patriarchal monotheism. When

the centaur told Jason that Medea had undergone a spiritual catastrophe

and the “opposite of a conversion,” he is perhaps speaking

to a majority of women today: Women are still to some degree traumatized

by the indifference of the world of Jason to their spiritual needs. The

very different kind of work pursued by Luce Irigaray—emerging from

postmodernist thought—and that of Starhawk—often dismissed

as “New Age”—both require that the patriarchal “God”

sit down at the table and hear the voices of other spiritualities, other

relationalities. The establishment of the “aboriginal feminine”

or goddess modality of spirit is an essential first step, but a more ambitious

goal is to see women reclaim all modalities of the spirit. The shamanic

anyway belongs equally to men and women, while warrior polytheism represents

a conquestial mode of divinization that women may need to draw on as much

as men. (All great art, reform, construction, and exploration need a spirituality

of courage and risk taking.) Monotheism as a relationship with a “wholly

other” is likewise a relational spirituality as potentially cornucopian

to the female spirit as the male. Finally, the transcendent modality of

the spirit requires that gender as a “modification of the mind”

is suspended altogether in ecstatic absorption (or enstatic as Feuerstein

prefers it). Why should women (or men, for that matter) be deprived of

any of these modalities of the spirit?

Bibliography

Baring, Anne, and Jules Cashford. The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution

of an Image. London: Arkana, 1993.

Barnet, Norman. Black Heroes and the Spiritual Onyame: An Insight

into the Cosmological Worlds of Peoples of African Descent. Cryodon:

Filament Publishing, 2005.

Eckhart, Meister. Selected Treatises and Sermons. London: The

Fontana Library, Collins, 1963.

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Bollingen

Series 76. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Ferrer, Jorge N. Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory

Vision of Human Spirituality. Albany: State University of New York

Press, 2002.

Feuerstein, Georg. The Yoga Sutras: A New Translation and Commentary.

Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, 1989.

Freke, Timothy, and Peter Gandy. The Jesus Mysteries: Was the “Original

Jesus” a Pagan God? New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden

Symbols of Western Civilization. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

Harner, Michael. The Way of the Shaman. New York: HarperSanFrancisco,

1990.

Hillman, James. Revisioning Psychology. New York: HarperPerennial,

1977.

Irigaray, Luce. Between East and West: From Singularity to Community.

New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Otto, Rudolf. The Idea of the Holy. London: Oxford University

Press, 1923.

Paper, Jordan. The Spirits are Drunk: Comparative Approaches to Chinese

Religion. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Pasolini, Pier Paolo. Medea (Maria Callas, Giuseppe Gentile).

Euro International Film (EIA) S.p.A., 1969.

Scholem, Gershom. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. New York:

Schocken Books, 1995.

Shlain, Leonard. The Alphabet versus the Goddess: The Conflict between

Words and Images. London: Penguin/Compass, 1998.

Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the

Great Goddess. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1999.

Stone, Merlin. When God Was a Woman. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, 1976.

Wilber, Ken. The Spectrum of Consciousness. Wheaton, IL: Quest

Books (The Theosophical Publishing House), 1993.

|

|