| |

|

Abstract

This paper presents the life, work, and context of British sculptor

Peter King (1928-1957). His untimely death meant that he has been largely

omitted from the history of 1950s British art, but recent discoveries

of missing works, diaries, photographic plates, and other memorabilia

indicate the significance of his work for the period. He was undoubtedly

a prolific artist, whose exceptional talent was recognised by Henry

Moore, who appointed him as his assistant along with Anthony Caro. King

was part of a group of artists associated with Moore’s studio,

with the teaching team at St Martin’s School of Art, with artists

living at the Abbey Art Centre in London, and with Victor Musgrave’s

Gallery One in Soho. He received the Boise Travelling Scholarship and

funding from the BFI for an animated film, and exhibited the film and

his work across Europe before succumbing to a blood-poisoning at the

age of twenty-nine.

In his short life, from 1927 to 1957, Peter King completed

a prodigious quantity of sculpture and works on paper. His trajectory

moves, after study at Wimbledon School of Art, from ‘academic’ sculptural

works and public monumental commissions, through very contemporary forms

of abstraction, to a quite destructive fluidity of form in his last

months. After the chaos of his last few years he left behind a widow

with two children and a mistress and son, who between them kept safe

a significant proportion of his collection.

[1]

Many works had been sold to private collectors, and

to the Arts Council, the British Council, and the Contemporary Arts

Society.

[2]

Many more works were destroyed, the bulk of these

scattered in the grounds of the seminal Abbey Art Centre artists’ commune

in High Barnet, London, which either rotted away, were stolen,

or – quite probably – landed up on the popular 5th November communal

bonfire. King as an artist largely disappeared from public and critical

view after his death.

It is only recently, with archival material

emerging from private sources, and from archives at TateBritain and

the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds that

the true picture of King’s place in British art of the 1950s is beginning

to emerge. The Henry Moore Institute has a collection of Peter King

memorabilia, donated, along with several of his works, by his widow

in 2002, while the British Museum

recently purchased several works on paper. Scholarly interest is growing,

and his name has appeared in recent publications.

[3]

In 2003 the Museum

of London showed his film The Thirteen Cantos of Hell, as part of a celebration of London artists’ quarters,

and King is mentioned in the accompanying book.

[4]

In 2004 Ian Barker, having drawn on the Henry Moore

Institute archive, made eight references to King in his volume on Anthony

Caro,

[5]

and in 2007 there were three references in a Henry

Moore Foundation book on Hoglands.

[6]

Most notable to date is the essay by Martin Harrison

in the Henry Moore Institute 2003 two-volume series on British sculpture.

[7]

In it Harrison describes King’s early monumental

work for Giudici stone-carvers, his appointment as assistant to Moore,

his first one-man shows at Gallery One, and the final anguished, dripped

and spattered head-forms created shortly before his death. Exhibitions

including works by King are now taking place on a regular basis.

[8]

As noted by the Museum

of London, King was embedded

in Soho, the creative quarter of London

in the 1950s.

[9]

Through its galleries, through St Martin’s where

he taught from 1953, and through his employment at Moore’s

Much Hadham studios, he came to know many of the key artists, curators,

and collectors of the time. He knew the artists of the New

Aspects of British Sculpture pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale.

[10]

This is remembered in terms of Herbert Read’s catalogue

essay, which introduced the term ‘the geometry of fear’, a term that

might usefully be applied to some of King’s work. In a private letter

Frank Martin, who hired King to teach bronze-casting at St

Martin’s, said that King ‘stood alongside the rest of my

team at that time, all emerging sculptors: Caro, Paolozzi, Frink and

Clatworthy.’

[11]

At Hoglands, Moore’s home and studio, King worked

with Caro, Alan Ingham and Peter Atkins. One of the major projects that

he worked on was the far-right of four enormous stone elements in Moore’s

Time-Life screen (former Time

Life Building, Bond Street, London, 1952-3), as part of a team that

included Bernard Meadows.

[12]

King cast two bronzes for Caro in the foundry he

built at the Abbey Art Centre,

[13]

and may have cast for Moore.

[14]

It was here at the Abbey Art Centre, in the early 1950s

that King made a close friend in the Scottish painter Alan Davie, met

F.N.Souza and others, including the ceramicists Lucie Rie and Hans Coper.

The art collector William Ohly opened the Abbey Art Centre in High Barnet,

North London in 1949. He was the owner

of the Berkeley Galleries, Davies Street, London,

where Rie and Coper had had an early exhibition together. King showed

early works there with other Abbey artists, alongside jewellery pieces

by Davie and cut-out figures

by Lotte Reiniger (1899-1981). King became a friend of Reiniger, the

animator, and her husband Carl Koch, a cinematographer who had worked

with Jean Renoir. Reiniger and Koch became godparents to King’s first

two children, and, crucially, Reiniger introduced King to the principles

of shadow-puppet animation later used by King in his film The

Thirteen Cantos of Hell. Through Victor Musgrave, the owner of Gallery

One, Litchfield Street,

London, King met Musgrave’s wife, the photographer

Ida Kar. Amongst the Kar archive at the National Portrait Gallery are

a series of photos of King and his work (fig. 1), including detailed

shots of him pouring bronze in his home-made foundry. Musgrave’s Soho

gallery happened to feature in a documentary film called Sunshine in Soho (Burt Hyams, 1956), which contains a few seconds

footage of King, talking to an elegant woman, possibly trying to persuade

her to buy one of his pieces.

[15]

As Musgrave wrote of King in his obituary in The Times: ‘His untimely death obscured

his importance in the setting’.

[16]

Caro commented that his death meant ‘a real loss

to English sculpture’.

[17]

In fact King’s work had appeared in a few shows after

his death, and in a highly modernist living room scene on the front

page of Ideal Home magazine in 1959. In 1961 two miniatures by King appeared

in a jewellery show organised by the Victoria

and Albert

Museum, alongside pieces from his mentor

in lost-wax casting, Alan Davie, and works by King’s sister-in-law,

the Viennese artist Angela Varga (born 1925).

[18]

Mostly, however, King remained unknown.

So, what was it about King’s brief trajectory of that

convinced some commentators – including Anthony Caro – that King would

have played an important role in British post-war sculpture, had he

survived? What were the landmark moments in his life? We start, according

to the recollection of his younger brother, Brian, with teenage years

of precocious and intense sculptural activity, along with a promiscuous

reading in religion, psychology and philosophy that quite baffled the

rest of his family. This is in fact a recent discovery: up to the year

2007 it was thought by his immediate estate that King conformed to the

stereotype of the intuitive but inarticulate artist. Instead, newly

discovered notebooks, a journal, and letters,

[19]

show him to be writing with the same intensity with

which he sculpted, drew, and painted. One notebook reveals his sculptural

working methods in short textual descriptions accompanying photos of

his work, while his densely written hundred and fifteen page journal

reveals the breadth of his reading, and the rather alienated state of

his mind towards the end of his life. As a teenager in 1942 he was evacuated

from London,

and in 1948 he joined Wimbledon School of Art. The exact chronology

of the following period still needs clarification, but it seems he spent

a traumatic year and a half in the Air Force, a satirical account of

which is found in his journal, during which time he may have taken LSD,

possibly obtained from US servicemen.

[20]

In 1951 or 1952 he moved to the Abbey Art Centre,

while working as a monumental mason for Giudici, and as assistant to

Sir Charles Wheeler (1892-1974). The quality of King’s work led to a

recommendation to Moore, who took him on as assistant in 1952, and in

1953 he joined Frank Martin’s teaching team at the St Martin’s School

of Art. Before

his death he had had two one-man shows and three group shows at Gallery

One, Soho, and completed the animated film The Thirteen Cantos of Hell (1956). In

receipt of a Boise scholarship, he exhibited

in Paris and Rome

in 1957. A motorcycle accident in 1955 cut short his employment by Moore and, as his personal

life spiralled out of control, he made an attempt on his life, dying

in 1957 of an illness contracted after the accident.

His short life, and his intense artistic relationship

with his mistress and fellow artist Shelagh Loader (Dates?: sorry, don’t

know when born, still alive now), during which time he produced important

work, draw comparisons with the even shorter, but perhaps equally turbulent,

life of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Loader’s role in his later work is not

clear at this point, but she was involved in the production of the film

and assisted King in his casting and other techniques in molten metal.

In a notebook King describes some of his work at Wimbledon

School of Art as ‘academic studies’, and so the term ‘academic’ could

be used for many of the works in this period. Other than that, dates

for his work are provisional at this stage, so one cannot suggest more

than ‘early’, ‘middle’, and ‘late’ periods to indicate the chronology

of his development.

The extensive experience that King had during his schooling

and subsequent employment with Giudici, referred to by the critic Lawrence

Alloway as ‘hack-work’, ensured a considerable technical fluency.

[21]

Harrison mentions that ‘among the commissions King

helped to carve’ was Wheeler’s allegorical Earth

and Water for the Ministry of Defence building

in Whitehall, London (1951-52).

[22]

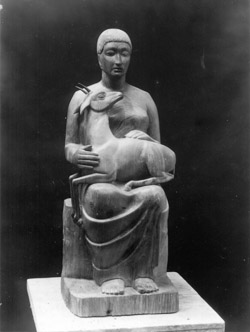

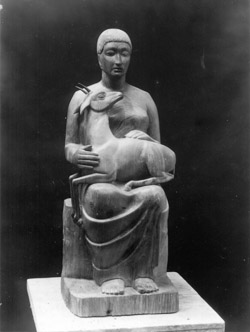

According to King’s brother, a technical proficiency

was obvious from early on in King’s life. A wood carving is thought

to have been made at the age of fifteen, in about 1943, some five years

before King enrolled at Wimbledon School of Art (fig. 2).

|  |

Fig. 2 PEK0187

This

wood carving is believed to have been carried out in King’s fifteenth

year. Height: ~75cm

Photo:

Peter King

Copyright:

Estate |

As well as a technical fluency in formal sculpture,

largely self-taught prior to the consolidation of his skills at Wimbledon,

King experimented with many materials, including Perspex stolen from

a nearby factory. He appeared in court as a result, but apparently so

intrigued the factory owner with the account of his technical innovations

with the medium, charges were dropped. King also gained considerable

skill with photography and amongst the surviving artefacts from his

life is an extensive collection of glass plates recording his work.

Figure 3 shows a commission for a school in Surrey, probably made before 1953. This photograph, found

on page 44 of King’s notebook, is captioned in his hand ‘Stone relief

on a Surrey County

Council School

4ft x 5ft’.

[23]

|  |

Fig. 3 PEK1454

This

photo is found on page 44 of King’s notebook, and is captioned

in his hand ‘Stone relief on a Surrey County Council School 4ft

x 5ft’ Another photo exists of the school building with the relief

in place.

Photo:

Peter King

Copyright:

Estate |

Once King moved into the Abbey Art Centre in 1951 or

1952 he was already pursuing a very personal experimentation and a move

to abstraction. This early period of King’s work was dominated by two

themes: figurative elements taken from ethnic art, and natural elements

as in objet trouvé. By moving into the Abbey Art Centre he came into the

orbit of its founder, Ohly, and his extensive collection of ethnic art

from Africa, Indonesia,

and Tibet. Some of

his collection was on display in a converted tithe barn, an old structure

directly opposite King’s studio. In the existing photographs King’s

studio appears cramped and densely packed with finished and half-finished

works. The photograph in Figure 4 was probably taken between 1951 and

1953, and shows a pair of figures on the left believed to have been

assembled from found branches and timbers taken from an old carriage.

|  |

Fig.

4

King’s Studio

This

photograph, by King, probably taken between 1951 and 1953, show

both the intensity at which he worked, and the dominant themes

of that period. The pair of figures on the left is believed to

have been assembled from found branches and timbers taken from

an old carriage.

Photo:

Peter King

Copyright:

Estate |

King had already made a journey from his assured classical

mastery to the most experimental of formats, though probably still executing

traditional commissions alongside his new experiments. His instincts

for technical mastery were now often directed at the problems of metal-casting,

using a home-made foundry in the garden of the Abbey Art Centre. He

may have learned the lost-wax casting technique for small-scale sculpture

from Alan Davie, a technique which King now adapted for larger-scale

sculpture. He also used other flammable materials that would be lost

in casting, including a bird’s nest carved into the shape of a face.

Other works of this period provide the bridge between

the overtly experimental and the classical tradition in which he was

so fluent, for example the torso shown in Figure 5. It shows the possible

influence of both Moore and Hepworth.

|

|

Fig. 5 PEK0059

Torso

in wood, 34 x 74 x 22 (cm)

Photo:

Mike King

Copyright:

Mike King |

The early experiments with found materials and assemblages

gave way to what could be called his mature or ‘middle-period’ style:

sculpture in bronze, aluminium, stone and plaster with a consistent

semi-relief treatment and a personal grammar of semi-geometrical abstraction.

Generally considered to be the iconic piece of this period, and one

of the few works with a name, Man with Cloak appeared on a Gallery One

invitation (fig. 6). Typical of work of this period, the front is worked

in detail, while the back is simply rounded off.

|

|

Fig.6 PEK0001 (Man with Cloak)

Wood, 59 x 94 x 24 (cm)

Photo:

Mike King

Copyright:

Mike King |

It is not clear why King moved from sculpting in the

round to this semi-relief treatment, but his experience of formal relief

work, and his extensive use of monotypes to explore his emerging sense

of line, may have been factors. In fact he produced huge numbers of

prints, mostly monotypes, of which many hundreds survive, and which

were integral to his artistic development. The monotypes have a strong

sculptural feel, complementing the frontal nature of the sculptures,

and there are a number of examples of close relationships between print

and sculpture. Figure 7 shows a monotype ‘sketch’ for the sculpture

in Figure 8, which was King’s submission for the TUC Congress House sculpture competition in 1955.

[24]

The number in the bottom-right corner may have been

stamped there by competition officials. James Hyman has suggested that

given its close resemblance the print came after the sculpture,

[25]

but there is evidence from other print-sculpture

pairings that it was the other way round.

|

Fig. 8 PEK0007

Composite

(possibly armature plus painted clay),

52 x 34 x 9 (cm) Entry

for TUC Congress House sculpture competition

Photo:

Mike King Copyright:

Mike King |

Given the apparent convergence between from-the-front

sculpture and in-the-round monotypes of this period, King’s next venture

seems a natural step: to take his sculptural forms and use them in an

animated film. His The Thirteen

Cantos of Hell was an adaptation of part of Dante’s Divine

Comedy, the purgatory section of which seemed to fascinate him.

The technique he used was the shadow-puppet and rostrum technique of

Reiniger, who taught him her methods in exchange for carpentry work

he carried out on her rostrum stand. However her precise role as a possible

mentor in animation is unclear. The Experimental Production Committee

of the British Film Institute gave King a grant of £500 for the film

and it was premiered the Hammer Theatre in May 1956, and shown at the

National Film Theatre, the Edinburgh Festival, Cannes, and other European

galleries. Figure 9 shows a still from the film, featuring a boat motif

that appeared in much of his work of the period. It is poignant, in

the light of his attempt on his life at the time, to note that The Thirteen Cantos of Hell ends with the

‘wood of the suicides’.

|

Fig. 9 Film still

Film

still, perhaps used in promotional material, from The Thirteen Cantos of Hell

Glass

plate, 24 x 16 (cm)

Photo:

Iby-Jolande Varga

Copyright: Iby-Jolande Varga |

The ‘late’ period of his work seems to veer between

a coherent culmination of his artistic trajectories, and nihilistic

and anguished sculpture and paintings, one of the latter being completed

in his own blood after slashing his wrists.

[26]

His extensive journal entries in this period provide

a picture of a mind on the verge of breakdown: brittle, intensively

creative and profoundly anguished. Loader describes the period as a

mutual exploration of Jung’s psychology and alchemical writings, resulting

in another new direction for King: an illustrated book called The

Ash of Mimir (fig. 12), a little reminiscent of Blake’s illuminated

writings. In King’s notebook there are exercises in calligraphy as a

preparation for this project, and some ruminations on the theme of ‘walking

with a squint’ – seemingly a reference to the way that his surroundings

could overwhelm him, and possibly a reference to Sartre’s Nausea

which had clearly made an impact on him. He also describes suburbia

as the ‘citadel of schizophrenia’, a phrase, it seems, of his own coinage,

but hinting at his state of mind. Two factors seem to have precipitated

this state of mind: firstly the genuine torment over the parting from

his wife and two young children, and secondly the motorcycle accident

in which he broke his leg. He made a poor recovery from this and was

sent for endless and inconclusive medical tests.

Figure 10 is of a painting made in this last period,

one of a series of over a dozen surviving works on paper depicting the

human head in a paroxysm of anguish. These were often painted on the

reverse of earlier monotypes, which, in some cases have been defaced,

presumably by King in moments of anger or depression.

|

|

Fig. 10 PEK0564

Paint

on paper 56 x 76 (cm)

Photo:

Mike King

Copyright:

Mike King |

His sculpture of the time was sometimes

destructive in both design and execution. This was particularly so of

work executed with a technique he had been working on for some time,

of throwing molten metal into sand, and drawing into sculptural forms

using a refractory implement. Musgrave had described this process as

‘action sculpting’ in a direct reference to Pollock’s action painting.

Sir Anthony Caro mentions that in a visit to the Abbey Art Centre at

this time, where he met Alan Davie and Peter King, he heard of a ‘new

American painter called Jackson Pollock’ and adds that ‘Peter was far

ahead of us all’.

[27]

In a notebook King describes this rather immediate

method of working in metal as follows: they were ‘produced by throwing

the molten metal on a bed of fire-resisting material, and manipulating

the metal before it sets. Each piece so produced is joined to the next

by thrusting the solid form in the molten mass of the next one, so building

up the desired structure’.

[28]

Figure 11 is of an aluminium piece built up in this

way, but including another of his innovations: the addition of molten

glass. This is one of the most considered thrown pieces of this later

period, others seem to be more spontaneous and chaotic.

|

|

Fig. 11 PEK0037

Figure,

aluminium and glass, 24 x 37 x 17 (cm)

Photo:

Mike King

Copyright:

Mike King |

King’s journal

may provide some guidance as to the influences on him,

[29]

though to mine its true significance a longer study

than this is needed. The journal has no dated entries at all, though

some of the books he refers to were only just in print during his last

years, and may help pin down the earliest possible dates for some passages.

A large section of the journal is devoted to a narrative and rather

ironic account of a call up to National Service and subsequent training,

interspersed with reminiscences of cinema attendance and other daily

activities. There are also substantial sections of commentary on art,

philosophy, religion, and psychology, which give us some idea of the

thinkers he had studied. In philosophy, psychology and religion they

were Lao Tse, Meister Eckhart, Henry Thoreau, Sigmund Freud, Jean-Paul

Sartre, C. G. Jung, Martin Buber, Soren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger,

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Rudolf Lotze, Nikolai Berdyaev, Emmanuel Mounier,

J. B. Coates, and Edward Glover. It seems that of all these it was Jung

who was the most important to him. In

art history and criticism they were Herbert Read and Lewis Mumford.

The opening pages of the journal record King’s response to Herbert Read’s

The Meaning of Art (1930)

by. King is particularly interested in how distortion of geometric form

works in aesthetics and how the degree of departure is ‘determined by

the individual instinctive expression’.

[30]

At times it appears from the journal that King is embarrassed

to be an intellectual: he ridicules intellectual activity as ‘fonting’.

[31]

It is clear, however, that he must have read widely

from an early age, and to some extent systematically. At the end of

the journal, at a time that may not have been too long before his death,

he had made a monthly reading list, indicating a determination to keep

abreast of new writing in art criticism, literature and philosophy.

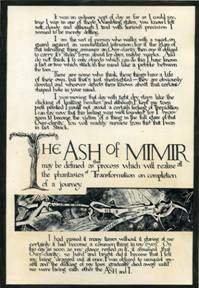

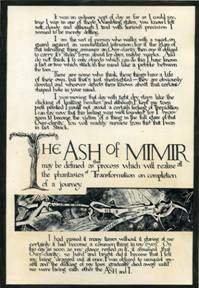

Apart from the narrative and commentary sections –

sometimes interleaved – there are also three poems, and an extensive

section towards the end on The

Ash of Mimir (fig. 12). King was clearly obsessed with the Norse legend

of Odin and his attempt to gain wisdom by hanging himself on the Ash

of Mimir, the world-tree, also known as Yggdrasil. King states in the

journal and on the frontispiece of The

Ash of Mimir: ‘The Ash of Mimir may be

defined as that process which will realise those fantasies of Transformation

on Completion of a Journey.’

[32]

It is not clear what King’s sources are for the legend,

though he may have first encountered the myth and its symbolism through

Jung. He cites paragraph 523 from Jung’s Symbols

of Transformation several times.

[33]

The Ash

of Mimir is an unfinished project consisting of five illuminated

pages, twelve additional illustrations, and some twenty-eight journal

pages of supporting text, though more related material may emerge in

time. More work is required on the transcription and interpretation

of these journal pages, but it is clear that King drew on the imagery

of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea in many descriptive passages.

|  |

Fig. 12 PEK0922 Frontispiece for The Ash of Mimir

Ink

and monotype on paper, 20.18 x 29.24 (cm)

Photo:

Mike King

Copyright:

Mike King |

This paper serves to amplify Harrison’s

2003 introduction to Peter King. The real work remains to form any significant

conclusions concerning King’s life and work, to evaluate his place in

British ’50s sculpture. Of the sculpture known to be lost but not necessarily

destroyed there remains the possibility of their discovery, as well

as hitherto unknown works. These may fill some of the gaps and help

in the chronology. The journal and letters need careful cross-referencing

with other accounts of King’s life, such as the written memoirs of his

widow, and oral accounts from others still alive who knew him. A thematic

study is required across the works on paper and the sculpture: once

it is possible, for example, to see all the horse-related representations,

or all the Stygian boats, collected together, much would emerge. King’s

ability to so dramatically distort human proportions while retaining

their integrity is also an issue worth pursuing across the collection:

his personal grammar of human gesture is intimately related to this.

At a purely technical level there are many unanswered questions as to

whether he independently discovered some of the unusual metal-working

techniques he deployed. Finally, the key questions of the influences

on and by him will need to be resolved. As Harrison

says, ‘it is hoped that appropriate recognition for this artist, now

long overdue, will soon be forthcoming’.

[34]

The scholarly work necessary for this recognition

now has significant resources waiting to be explored.

(3726 words)

Acknowledgements

The author would

like to thank the Art and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding

the digitisation project, and London

Metropolitan University

for support. The digitised archive is now online at the Visual Arts

Data Service at vads.ahds.ac.uk/collections/PKA.html and at

www.peterkingsculptor.org.

References

[1]

At the time of

writing there are over a thousand works recorded in the Peter King

archive (available online via the Arts and Humanities Data Service);

over a hundred items of memorabilia that help chart the course of

his life and work; and a number of letters. The known works include

223 works and records of a further 123 that are either lost or destroyed;

618 works on paper; 45 puppets made of hinged card, many of which

are weighted with lead; and two prints of the 16mm film The Thirteen Cantos of Hell. The exact dates of most works are not

known, and he signed almost nothing and gave his pieces no names.

At present they have only four-digit accession numbers. Hence there

remains a considerable task to locate work within precise years and

months, beyond the crude division presented here of four main periods.

[2]

A letter from the Contemporary Arts Society, dated 17

June 1997 states: ‘Further to your enquiry regarding the whereabouts

of work by Peter King, the Contemporary Arts Society purchased the

following work from the artist and presented it to the following museum

collection. Series of Drawings, 1954 … Presented to Birmingham

Museum and Art

Gallery, 1959.’

(Letter in possession of the Estate of Peter King, hereafter Artist’s

estate)

[3]

Starting with a mention in Roger Berthoud’s Life of

Henry Moore (1987). This is now found in the revised edition:

Berthoud, R., The Life of Henry

Moore, London: Giles de la Mare

Publishers, 2003, p. 303

[4]

Wedd, K., et al, Creative

Quarters – The Art World in London

from 1700 to 2000, Museum

of London: Merrell,

2001, p. 135

[5]

Barker, I., Anthony Caro – Quest for the New Sculpture,

Kunzelsau: Swiridoff Verlag, 2004

[6]

Mitchinson, D., et al, Hoglands – The Home of Henry and Irina Moore, Aldershot:

Lund Humphries, 2007, pp. 73, 77, 90

[7]

Curtis, P., et al, Sculpture

in 20th-century Britain

Vol 2, Leeds: Henry Moore Institute,

2003, pp. 191-193

[8]

Recent shows include: Museum of London, ‘Creative Quarters’,

June-July 2001; Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, ‘Sculpture in 20th Century

Britain’, September 2003-March 2004; Modern British Artists, 20/21

British Art Fair, London, September 2006; Robin Katz Gallery, May-July

2007; Henry Moore Institute Library, Leeds, November 2007-January

2008; England and Co. Retrospective, March-April 2008; Abbey Art Centre,

July 2008; British Museum, ‘British Sculptors’ Drawings’ from September

2008 to January 2009. Planned shows include Jonathan Clarke Fine Art,

London, the Lotte

Reiniger Museum,

Tübingen, Germany,

and a second solo show at England and Co.

[9]

Wedd, Kit, et al, Creative Quarters – The Art World in

London from 1700 to 2000, (Museum

of London) London: Merrell, 2001, p. 135

[10]

Robert Adams, Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick,

Geoffrey Clarke, Bernard Meadows, Eduardo Paolozzi and William Turnbull.

[11]

Letter from Frank Martin to Liz Sheppard, dated 26 February

1985; Henry Moore Institute Archive, Leeds

[12]

Barker, as at note 5, p. 50

[13]

King cast Caro’s Woman

Walking Along and Acrobatic

Figure, 1951-55, Barker, Ian, Antony

Caro: Quest for the New Sculpture, Kunzelsau: Swiridoff Verlag,

2004, p. 59

[15]

The film is in the BFI Archive, London .

[16]

The Times,

5 November 1957

[17]

Letter from Caro to King’s widow, dated 1 November 1957,

in Henry Moore Institute, Leeds,

archive.

[18]

In 1993 George Melly wrote to King’s widow that he was

impressed with photos of the work she had sent to him, letter to Katharine

King, 29 March 1993, Artist’s estate

[19]

Some letters are in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive

at Much Hadham, others in the Artist’s estate

[20]

This claim is made by King’s brother, but the only other

evidence for this might be in King’s journal writings which bear a

resemblance at times to Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea,

alleged by Simone de Beauvoir to have been written after a bad mescaline

trip.

[21]

Art News, February

1955, Vol. 53, No. 10, p. 68

[22]

Harrison, M., ‘Peter

King’ in Curtis, as at note 7, p. 191

[23]

Another photograph exists of the school building with

the relief in place, in notebook; artist’s estate.

[24]

As is well known the commission eventually went to Jacob

Epstein and Bernard Meadows.

[25]

Private conversation.

[26]

Conflicting accounts of this event exist.

[27]

Private correspondence, 9 April 1997. See also Barker,

as at note 11

[28]

King, journal,

p. 14; Artist’s estate

[29]

The Peter King Estate is indebted to Betty MacAlister

and Jackie Howson at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

for the transcription of the journal.

[30]

King, journal, p. 1; Read, Herbert, The Meaning of Art, London: Faber and Faber, 1972, pp 28-32

[31]

A creature that intellectualises as a pastime is ridiculed

by King as a ‘glub of font’ and compared to a grotesque insect that

carries a huge egg sac around with it: King, journal, p. 77

[32]

King, journal,

p. 98

[34]

Harrison, as at note

7, p. 193

|

|